PRECARIOUS PUBLISHING IN LATIN AMERICA

If you find yourself in a big Latin American city like Buenos Aires, Mexico City, or São Paulo, chances are it won’t be long before you come across a cartonero, a pepenador, or in Portuguese, a catador. Pulling a rough and ready handmade cart, cartoneros (waste pickers) sort through everyday refuse, collecting different types of recyclables, including glass, aluminium and cardboard, and make a living by selling these materials, in many cases, to cartonero-specific recycling cooperatives. In the highly stratified urban environment of São Paulo, cartoneros are ever present, and yet also invisible to some, stigmatised through a classic series of pure/impure binaries, and relegated to social categories that leave them open to violence and repression.

What’s interesting about the urban spaces in which cartoneros live and work, is that the very environment that creates such conditions of domination, exploitation and segregation is also simultaneously a space of extraordinary social experimentation and creativity. The cartonero is an index of a process but also an active agent within it; a figure who is traversed but also traverses the multiple flows of the city as these currents diverge, cross and come together.

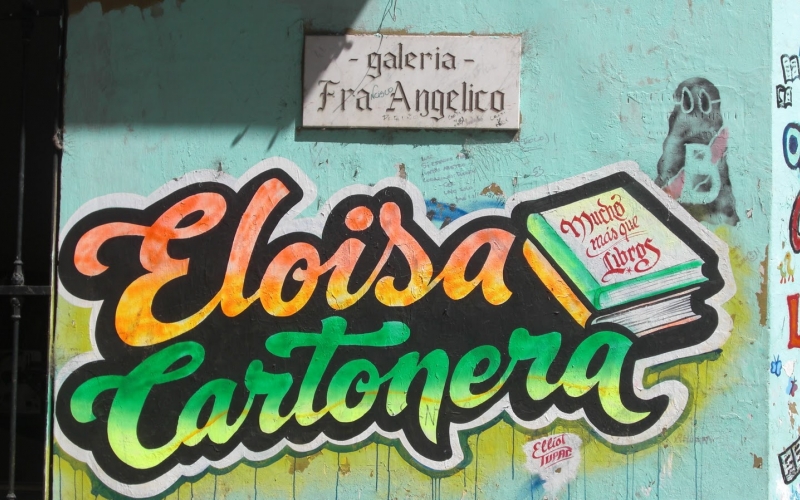

How are these spaces for encounter created? The 2001 economic crisis in Argentina put millions out of work and led to a huge increase in the number of cartoneros in Buenos Aires. In solidarity with the waste pickers, and as an attempt to democratise literature amidst the crisis, the founding members of Eloísa Cartonera began buying cardboard from the cartoneros to produce hand-painted books in 2003.

![Photo by Daniel Mundo]()

The publishing movement that Eloísa inspired became known as editoriales cartoneras (cardboard publishers or waste-picking publishers) and has spread across and beyond Latin America. Books produced range from children’s literature to experimental fiction, encompassing everything from fine art to Foucault and Zapatista political theory. But beyond the means of production there is also an ethos that Washington Cucurto, one of the founders of Eloísa, believes links such projects: a way of seeing cultural production as more fluid, more spontaneous: an audacity rooted in precarity.

In January 2017, Lucy Bell and I were successful in our application for an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Research Grant to work with these precarious publishers. We come from different backgrounds: Lucy is a Latin Americanist, strong on literary analysis and Mexico, while I’m an anthropologist specialising in social mobilisation and contemporary art in Brazil. Our project seeks to understand two main questions. First, to what extent is cartonera publishing a social movement, given that it has spread right across Latin America, and how does it inform our understandings of social movements and activism? Cartonera publishing actors and cartoneros themselves might not be taking part in traditional forms of mass mobilisation, but maybe this hints towards the potential of different kinds of activist strategies in precarious contexts.

Second, we’re interested in understanding the role of the book itself, as an art object and text, in the creation of new relations, communities and meaning. Cartonera books are beautiful, unique, and hand painted. They are aestheticised objects that cut through the multiple layers of social stigma that contextualise their production. From a recycling co-op beneath a six-lane flyover, to prestigious contemporary art biennials, to the shimmering glass and polished concrete of a museum like MAR in Rio de Janeiro, the journey of these objects and the people that produce them points to questions that make a fascinating research project.

An example of how these objects bring together different spheres can be found in the collaboration between Dulcineia Catadora (a key cardboard publisher in Brazil), the Occupation Hotel Cambridge, and the artist Ícaro Lira. Situated in a 15-storey building in central São Paulo, the Hotel Cambridge occupation hosts an artistic residency in which Lira was one of the first participants. One of his programme’s first initiatives was to invite Dulcineia to conduct workshops with the children of the Hotel Cambridge, producing book covers for a publication that would document their experiences of life in the occupation.

As Brazil enters what has been described as its worst economic crisis for a century, the precarity of such attempts is thrown into sharp relief. While the Hotel Cambridge may have gained a degree of legitimacy, the Baixada do Glicério recycling cooperative in São Paulo, a centre of cartonero activity and the operational base of Dulcineia, is currently being threatened with eviction by a new mayor, determined to ‘clean up’ the city. The ephemeral nature of cardboard publishing lends this research a sense of urgency and the project, initially conceived in September 2015, will start in October 2017.

Working alongside editoriales cartoneras, the potential for dialogue between literary analysis and ethnography points this project toward an interesting methodological framework. Close textual analysis will complement anthropological fieldwork allowing us to conceptualise meaning, relations, and worlds through the imagery, narrative and fiction that are presented by the cartonera texts. Another potential space of dialogue is located in literary works’ power of suggestion. Much of ethnography is situated between what can and cannot be said, and we will look to literary approaches to allow us to work towards the invisible, the unutterable, and what cannot be observed, perhaps foregrounding elements that are not apparent in the day-to-day practices that ethnography accompanies. These vanishing points of subjectivity matter to us as our aim is to grasp how new relations and communities can open ephemeral but powerful spaces to imagine and enact social change. We believe that by working with these fragile books, bound with recycled cardboard, printed on recycled paper, and often produced from photocopies, we can glimpse the subjective beginnings of an alternative imaginary, through which different futures can be perceived and enacted.

This article originally appeared on Allegra lab, May 16, 2017

What’s interesting about the urban spaces in which cartoneros live and work, is that the very environment that creates such conditions of domination, exploitation and segregation is also simultaneously a space of extraordinary social experimentation and creativity. The cartonero is an index of a process but also an active agent within it; a figure who is traversed but also traverses the multiple flows of the city as these currents diverge, cross and come together.

How are these spaces for encounter created? The 2001 economic crisis in Argentina put millions out of work and led to a huge increase in the number of cartoneros in Buenos Aires. In solidarity with the waste pickers, and as an attempt to democratise literature amidst the crisis, the founding members of Eloísa Cartonera began buying cardboard from the cartoneros to produce hand-painted books in 2003.

The publishing movement that Eloísa inspired became known as editoriales cartoneras (cardboard publishers or waste-picking publishers) and has spread across and beyond Latin America. Books produced range from children’s literature to experimental fiction, encompassing everything from fine art to Foucault and Zapatista political theory. But beyond the means of production there is also an ethos that Washington Cucurto, one of the founders of Eloísa, believes links such projects: a way of seeing cultural production as more fluid, more spontaneous: an audacity rooted in precarity.

In January 2017, Lucy Bell and I were successful in our application for an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Research Grant to work with these precarious publishers. We come from different backgrounds: Lucy is a Latin Americanist, strong on literary analysis and Mexico, while I’m an anthropologist specialising in social mobilisation and contemporary art in Brazil. Our project seeks to understand two main questions. First, to what extent is cartonera publishing a social movement, given that it has spread right across Latin America, and how does it inform our understandings of social movements and activism? Cartonera publishing actors and cartoneros themselves might not be taking part in traditional forms of mass mobilisation, but maybe this hints towards the potential of different kinds of activist strategies in precarious contexts.

Second, we’re interested in understanding the role of the book itself, as an art object and text, in the creation of new relations, communities and meaning. Cartonera books are beautiful, unique, and hand painted. They are aestheticised objects that cut through the multiple layers of social stigma that contextualise their production. From a recycling co-op beneath a six-lane flyover, to prestigious contemporary art biennials, to the shimmering glass and polished concrete of a museum like MAR in Rio de Janeiro, the journey of these objects and the people that produce them points to questions that make a fascinating research project.

An example of how these objects bring together different spheres can be found in the collaboration between Dulcineia Catadora (a key cardboard publisher in Brazil), the Occupation Hotel Cambridge, and the artist Ícaro Lira. Situated in a 15-storey building in central São Paulo, the Hotel Cambridge occupation hosts an artistic residency in which Lira was one of the first participants. One of his programme’s first initiatives was to invite Dulcineia to conduct workshops with the children of the Hotel Cambridge, producing book covers for a publication that would document their experiences of life in the occupation.

As Brazil enters what has been described as its worst economic crisis for a century, the precarity of such attempts is thrown into sharp relief. While the Hotel Cambridge may have gained a degree of legitimacy, the Baixada do Glicério recycling cooperative in São Paulo, a centre of cartonero activity and the operational base of Dulcineia, is currently being threatened with eviction by a new mayor, determined to ‘clean up’ the city. The ephemeral nature of cardboard publishing lends this research a sense of urgency and the project, initially conceived in September 2015, will start in October 2017.

Working alongside editoriales cartoneras, the potential for dialogue between literary analysis and ethnography points this project toward an interesting methodological framework. Close textual analysis will complement anthropological fieldwork allowing us to conceptualise meaning, relations, and worlds through the imagery, narrative and fiction that are presented by the cartonera texts. Another potential space of dialogue is located in literary works’ power of suggestion. Much of ethnography is situated between what can and cannot be said, and we will look to literary approaches to allow us to work towards the invisible, the unutterable, and what cannot be observed, perhaps foregrounding elements that are not apparent in the day-to-day practices that ethnography accompanies. These vanishing points of subjectivity matter to us as our aim is to grasp how new relations and communities can open ephemeral but powerful spaces to imagine and enact social change. We believe that by working with these fragile books, bound with recycled cardboard, printed on recycled paper, and often produced from photocopies, we can glimpse the subjective beginnings of an alternative imaginary, through which different futures can be perceived and enacted.

This article originally appeared on Allegra lab, May 16, 2017

auflynn [at] arts.ucla.edu

Alex Ungprateeb Flynn is an Associate Professor at the Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles. Working as an anthropologist and curator, Alex’s practice explores the intersection of ethnographic and curatorial modes of enquiry. Researching collaboratively with activists, curators and artists in Brazil since 2007, Alex explores the prefigurative potential of art in community contexts, prompting the theorisation of fields such as the production of knowledge, the pluriversal, and the social and aesthetic dimensions of form.